Have you ever considered a career in archival work? This week, we’re publishing a two-part post by Dr. Greg Bradsher remembering one of NARA’s archivists.

The National Archives and Records Administration has been very fortunate to have among its ranks many “giants” of the archival profession. It has also had its share of interesting characters. Leonard A. Rapport was both. Of course Leonard would have never considered himself a giant in his profession. Interestingly enough, as Leonard himself pointed out in a 1987 address, “I survived the 35 years and a day without ever having an archival course, in or out of the National Archives.” Yet, his impact on the archival profession has been substantial. He was the first recipient of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) Award for Lifelong Service to the Archival Profession.

I got to know Leonard the year I began working at the National Archives. At that point, I simply knew him as an expert on the appraisal of records. As the years went by I learned that he was knowledgeable about a whole variety of historical and archival subjects. Whenever he asked me what I was working on and I told him, he would proceed to tell a story about the subject, often involving himself. He seemed to know everything and everybody. And in some respects he did.

On one of my first encounters with Leonard he told me he was going at lunchtime to a Salvation Army clothing store near Union Station and asked if I would like to go with him. He explained that with the exception of his underwear, that was where he obtained all of his clothing, including the Army jacket he was then wearing. I agreed to go. On the walk to the store I told him I had recently seen on television the movie The Bridge at Remagen, based on the 1957 book of the same name by Congressman Ken Hechler. Leonard nonchalantly responded that for years he had tried to find Heckler a wife. Before I had a chance to ask a question on that matter, Leonard was off on another story.

Leonard, born in Durham, N.C., in 1913, studied at the University of North Carolina (UNC) with R.D.W. Connor, who in 1934 became the first Archivist of the United States. After graduating in 1935, Leonard worked for the UNC Press and wrote fiction on the side. One of his short stories was reprinted in Best Short Stories of 1937. From 1938 to 1941, he participated in the Southern Writers’ Project, interviewing colorful figures in North Carolina. Several of his oral histories were printed in A Treasury of Southern Folklore, First-Person America, and other publications.

He served in the Army from 1941 to 1948, serving as a lieutenant with the 101st Airborne Division. In 1948, he collaborated with Arthur Northwood Jr. to publish the well-received book, Rendezvous With Destiny: A History of the 101st Airborne Division. In October 1949 he joined the National Archives. Using the G.I. Bill, he received his master’s degree in history from George Washington University in 1957. The following year he became the associate editor of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Federal Constitution and the Bill of Rights, a National Historical Publications Commission (NHPC) project.

During the next eleven years he worked in upwards of 200 repositories, filming thousands of pages of newspapers, imprints, and documents. He eventually bought a 1963 VW van whose previous owner had converted it to a home-made camper. In it Leonard carried a portable microfilm camera and film, as well as a small standard film camera, a portable dark room with developing supplies, two typewriters, a reference library, and a refrigerator for both bulk film and beer. During this project he took on the additional responsibility of searching for documents relating to two other NHPC projects, the documentary histories of the First Federal Congress and the First Federal Elections.

In 1969 Leonard returned to the National Archives. The following year Prologue published his article: “Printing the Constitution: The Convention and Newspaper Imprints, August–November 1787.” Then it was back to archival work, becoming the deputy director of the records appraisal staff. Maygene Daniels in her 1995 Society of American Archivists presidential address recalled: “I remember many happy hours, typically on Friday afternoons, in the old records appraisal offices, when Leonard would instruct us all on the fine points of the use of ‘that’ and ‘which’ in the English language. He would also read aloud portions of certain selected addresses of past SAA presidents from ‘the early days’…to illustrate various human foibles and foolishness.” She also noted that at one SAA annual meeting, “noting that all of the elected brass had name badges with enough ribbons to win the war in the Pacific, Leonard added one simple addition to his collection which many of you remember: ‘Best of Breed.’ After that, this organization eliminated all but a few ribbons on meeting name badges. As Leonard often observes, a bit of comedy may have more impact than a learned paper.”

Leonard’s output of literature during the 1970s included his Dumped from a Wharf into Casco Bay: the Historical Records Survey Revisited (1974) and Fakes and Facsimiles: Problems of Identification (1979), dealing with the forgery of manuscripts.

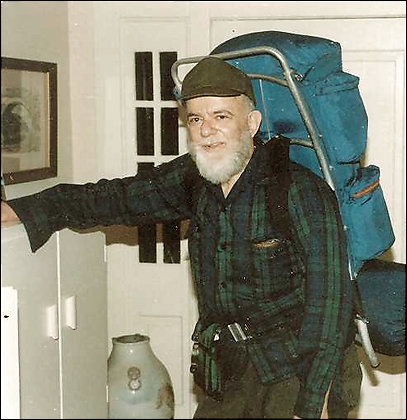

The 1980s for Leonard were just as busy and rewarding for him as were the previous decades. The American Archivist published his highly acclaimed article “No Grandfather Clause: Reappraising Accessioned Records” in 1981, which is still required reading in many archival courses thirty years later. The following year Leonard hiked the Appalachian Trail from Virginia to Asheville, North Carolina, to attend his 50th high school reunion. In 1984, the bicentennial program of the National Endowment for the Humanities gave a grant to a project sponsored jointly by the American Historical Association, the Library of Congress, and Project ’87, to collect and publish constitutional convention documents not published earlier by Max Farrand. Jim Hutson, head of the Library of Congress’s manuscript division was to edit the material and the Yale University Press was to publish them, as it had the Farrand edition in 1911. This was a project that Leonard knew back in the 1960s would sooner or later be attempted. He was prepared, as he had begun collecting copies of relevant documents back when he left the ratification project and returned to the National Archives.